Afua Hirsch: Our parents left Africa – now we are coming home

When I was a teenager, my mother overheard me telling my peers that I was Jamaican, a clearly absurd statement from a half-Ghanaian, half-English girl whose first name is one of the most common in a major African language.

My mother, born and raised in Ghana, was mortified. Although in part I was living out the now well-documented struggle of mixed race youngsters to grasp their identity, mainly I was just embarrassed. It wasn't cool to be African in those days and in my ignorant teenage way, I was acting out a much bigger crisis of confidence, one that had been swallowing Africans and spitting them out as permanent economic migrants in Europe and America ever since the end of colonialism.

My family left Ghana in 1962, and in those days, leaving was permanent. Flights were few and expensive and spare cash was instead sent back home, establishing a remittance economy that exists to this day. Life abroad, in London in the case of my mother's family, meant access to a stable income, reliable healthcare, plentiful food and a credible education. Meanwhile, many African states began falling apart.

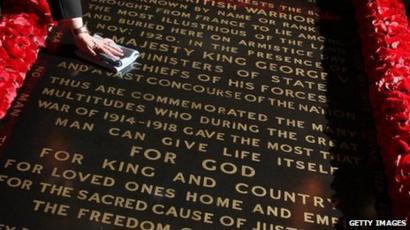

The 90s, when I was so quick to deny any association with Africa, was the decade when wars from Sierra Leone to Rwanda formed one of the most lethal periods in African history since the end of the slave trade. It culminated in the Economist dedicating a notorious cover in 2000 to what it described as "the hopeless continent", claiming that across Africa "floods, famine… government-sponsored thuggery, and poverty and pestilence continue unabated".

Revolving door alternations between civilian and military rule continued in countries ranging from Nigeria to Burundi, Chad to Congo. The World Bank was offering financial bailouts, but with the condition that countries accepted the humiliating label of "highly indebted poor country". In Ghana HIPC, as it was popularly known, became a term of derision and a symbol of battered pride.

The sparkling literary talent Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has said: "If I had not grown up in Nigeria, if all I knew about Africa were from popular images, I, too, would think Africa was a place of beautiful landscape, beautiful animals and incomprehensible people fighting senseless wars, dying of poverty and Aids, unable to speak for themselves and waiting to be saved by a kind white foreigner.

"The consequence of the single story is this," Adichie continues. "It robs people of dignity."

For many Africans, the whole ideology that the western world was more sophisticated became internalised into a kind of inferiority complex. One of my uncles, when he returned to London after a period of schooling in Ghana, simply exclaimed: "Back to civilisation." Anyone who could left and the subsequent brain drain only served to make matters worse.

The flight of Africans from their own nations fuelled cartoon-like perceptions of the continent abroad, in which the Economist was far from alone. And this was the context in which I grew up. Pretending to be Jamaican seemed a sensible solution at the time.

For my mother, that was the wake-up call she needed to organise our first trip to the west African land of her birth, an essential re-education in our roots. In 1995, we visited the Ghanaian capital, Accra, for the first time. I remember the usual things that people comment on when visiting equatorial African nations for the first time – the assault of hot air when stepping off the plane, which I confused with engine heat, the smell of spice and smoked fish on the air, and – most significantly for me – the fact that everyone was black. It sounds obvious but I had never really seen officials in uniform – immigration authorities, police, customs officers – with black skin. I don't think I had realised that there was a world in which black people could be in charge.

That first trip shaped my future in ways I could never have imagined. In the almost two decades that followed, I have moulded all educational and professional decisions into the form of a road that would lead me back to Africa. I devoured African literature, studied African politics, wrote my thesis on African women and political power, worked in development, law and now journalism, all with a focus on Africa. A decade ago, a job with an international development foundation led me to Senegal, where I lived for two years. Then, in February, I moved to west Africa for the second time, now setting up shop in the city of my very first trip to the continent, Accra.

Friends and relatives in the UK, even those who share my Ghanaian heritage, have repeatedly expressed astonishment at my desire to live in Africa. But the view from Ghana could not be more different. Far from being original, I find myself part of a narrative told with increasing fluency, as a steady stream of other European and American passport holders of African descent arrive at Ghana's Kotoka International airport, collect their worldly possessions from shipping containers at Tema port and search for homes in Accra's popular residential areas – Cantonments, East Legon and the Spintex Road.

They pay up to two years' rent upfront in dollars, at London prices, and find jobs with the growing number of international companies and professional service providers in Ghana or, more commonly, start their own business. At some point, this ceased to be an individual journey and instead became a phenomenon with its own label – "returnee".

There is a symmetry to the journey that returnees are making, which speaks volumes about the state of Africa today. Our parents left – exactly 50 years ago in my case – fleeing deteriorating economic conditions and limited opportunities at home. Now their children are forming an exodus from the crisis-ridden eurozone, four years of recession and the dogged perception of inequality and discrimination in the west. "Who needs the glass ceiling when you could be running your own business in one of the world's fastest-growing economies, enjoying the warm weather and surrounded by your own people?" one returnee to Ghana told me. "There is no contest."

The facts about Africa's change in fortunes are dazzling. Dubbed the "next Asia" for its rapid growth, the IMF forecasts that seven of the world's fastest-growing eco

nomies over the next five years will be in Africa; Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Congo, Ghana, Zambia and Nigeria are expected to expand by more than 6% a year until 2015.

The resource-rich continent has benefited from a boom in commodity prices, ranging from cocoa to gold, but has also increased manufacturing output, which has doubled over the past decade. Surveys by firms such as Ernst & Young, Goldman Sachs and McKinsey all describe how the telecom, banking, retail, construction and oil and gas industries are booming, sending foreign direct investment to dramatic new highs, while themselves representing an eagerness among global firms to attract business in Africa.

In Ghana, whose economy is one of the strongest, with current growth of around 9%, the City of London is arriving in force. Investment banks, magic circle law firms and international consultancies are permanent fixtures at Accra's plush hotels, where they are literally queuing up to tout for business.

With the growth in GDP comes a burgeoning middle class. The number of households earning more than $3,000 per year is expected to reach 100 million by 2015, putting the continent on a par with India. A recent report by the African Development Bank on Africa over the next 50 years predicts that "most African countries will attain upper middle income status, and the extreme forms of poverty will have been eliminated".

It's hard to overstate the impact of mobile technology on this transformation. Mobile penetration in Africa is now around 50%, forming the fastest-growing mobile market in the world. There are 100 million in Nigeria alone, a country that 20 years ago had only 100,000 phone lines. Telecoms companies now compete fiercely for almost 700 million consumers, not just to make calls, but for mobile money transfers, banking or even tracking agricultural and commodities data for farmers.

Seven per cent of Africans have access to broadband, but this is expected to reach 99% by 2060. New infrastructure such as the fibre-optic submarine cables now connecting south and east Africa, and due to connect west Africa this year, are playing a role in transforming productivity and making online technology realistic for African nations.

There are comical collisions between new technology and old problems. In Ghana, whose impressive GDP growth has not been met with the requisite increase in national grid capacity, people are using Twitter to monitor the frequency of power outages. "Lights off", as it is colloquially, almost affectionately known, is endemic in many countries. Ghana's power failures pale in comparison to Nigeria, where Lagossians say that if they have four hours of continuous mains electricity, then it is a good day.

These contradictions are the reality in most African countries. Economic growth is neither designed nor distributed evenly. And, in reality, it has not been matched by the kind of improvement in living conditions that many of my grandparents' generation expected when they witnessed independence from colonial rule.

The reality is that many African governments still serve primarily as agencies for the distribution of foreign aid. As the Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda has said: "Most of the rich countries are attracted to Africa's poverty rather than its wealth. And in the process they end up subsidising our failures, rather than rewarding our accomplishments."

There is plenty of poverty to be attracted to. Average life expectancy is still only 56 years, child mortality remains high at 127 per 1,000 live births in 2010, and overall literacy rates are only 67%. Africa's economic growth is often described as "jobless" for its failure to create jobs, in particular for the 60% of Africans aged between 15 and 24 who are unemployed and who, a recent report found, have given up on finding work.

With these seemingly incompatible realities existing side by side, there is increasingly a PR war for the image of Africa overseas. The Economist, still apologising for its "hopeless continent" issue in 2000, recently branded Africa "hopeful" instead. Most international news outlets now have programmes or seasons specifically designed to champion positive news stories in Africa. The BBC runs African Dream, a series about successful African entrepreneurs, while CNN has African Voices.

But it is not the role of the media to sell a rebranded version of Africa, any more than it was right to paint it as the heart of darkness in the past. The problems remain and they are real. Since I moved to Ghana in February as west Africa correspondent for the Guardian and Observer, there have been two military coups. Everyone living in Ghana – rich and poor – is lumped together in a permanent jumble of terrible traffic, unreliable water and frequent power outages. Poverty is real here, there is hunger and disease, and there is no welfare state. Far from setting out policies that promise any real social change, many African governments are focused instead on administering foreign aid and directing showcase infrastructure projects that do little to benefit ordinary people.

As a journalist, I navigate both these worlds, and it is not always easy. When I wrote an Observercolumn about attitudes towards sex in Ghana, I was bombarded with criticism from both ends of the spectrum. On one side, Ghanaians claimed I perpetuated outdated stereotypes by describing sex as taboo and often transactional in nature. On the other were NGO workers who complained that I had failed to mention female genital mutilation and maternal mortality, in their view central features of the African sexual experience.

The battle for the image of Africa – helpless and underdeveloped versus rapidly emerging economic giant – often gets personal. Journalists frequently, and rightly, draw criticism for describing a continent of 54 nations and breathtaking diversity as one country. But some commentators are quick to employ a definition of what it means to be African that excludes returnees like me for being too fair-skinned, too British or too westernised.

But being African is an increasingly complex identity. As someone who has been told she is too black to be British, and too British to be African, I am strongly against the notion that identity can be policed by some external standard. And I am not alone. The term "Afropolitan" is beginning to enter the mainstream; one definition describes it as: "An African from the continent of dual nationality, an African born in the diaspora, or an African who identifies with their African and European heritage and mixed culture.

"It doesn't matter whether they are born abroad or not; the important thing is their global perspective on issues, as well as their mixed cultural identity."

The enthusiasm with which people of African heritage around the world are embracing their roots has reached the level of a cultural resurgence. In stark contrast to my teenage Africa-denial, a significant number of international cultural icons are now African. The black British music scene is dominated by rappers with Ghanaian heritage – Tinchy Stryder, Dizzee Rascal and Sway. Azonto, a popular Ghanaian dance, has begun colonising clubs in London, a growing number of which now include Afrobeat on regular rotation.

This is not to dismiss the inequalities that still exist between Africa's increasingly visible international, urban elite – a category many returnees fall into – and the vast majority of Africans.

The reality is that, on so many levels, access to the west is still a fault line for determining privilege. For example, entrepreneurs in west Africa currently find that borrowing money for their businesses typically comes with interest rates of up to 30%, an unrealistic burden by any standard. Returnees, on the other hand, who have access to loans from foreign banks, can enjoy single-digit interest rates, effectively dominating local markets.

Africa is entering its new dawn, like all societies, with these divisions and inequalities as part of the story. For me, there is a very literal sense with which the past meets the future. On the weekends, from my home in Accra, I often visit a town in the mountains behind the city – Aburi – where my ancestors lived. My grandmother tells me the story of how her grandmother used to roll palm oil in barrels down the hill and on to the coast. These days, I like to visit a restaurant there, set up by a British Ghanaian returnee, and eat Ghanaian food – or pizza, depending on my mood – alongside so many other fugitives from the polluted city, enjoying the cool mountain air.

When she reached the ocean, my great-great grandmother would board a boat westwards along the coast to Takoradi, where she was from. These days, Takoradi is a hub of activity for barrels of a different kind of oil – crude – which have transformed Ghana's economy into one of the fastest growing in the world. I think she would be happy that her great-great granddaughter had returned to see that transformation for herself.