Aberfan disaster: Marking 54 years since disaster struck the south Wales village

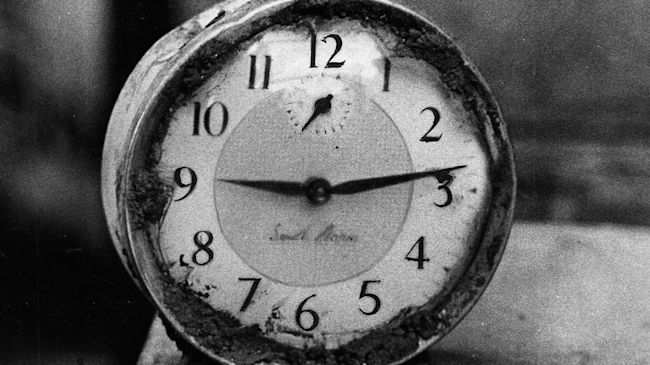

It was a Friday morning on October 21, 1966, shortly after 9:00 a.m. In the South Wales coal mining village of Aberfan, students at the Pantglas Junior School had just began their day's lessons after singing the hymn "All Things Bright and Beautiful," as they did on every other school day before it.

And then, as a woman who lost both her brother and sister in the disaster told England's Channel 4 News in 2016, there was "just a traumatic loud, loud banging noise, and it just got louder and louder and louder. Something was coming." The approaching sound was in fact a landslide of liquified coal waste descending down a mountain slope above, and it decimated several farm cottages on the slope before it reached the school.

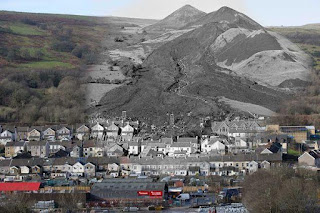

There had been weeks of heavy rainfall in the village, according to The Independent, and rainwater had saturated the colliery tip. For those whose knowledge of mining could fit in a thimble (ahem), a colliery tip is a pile made of spoil—a.k.a. coal mining waste material—and the rain buildup caused that particular colliery tip to collapse. The ensuing slurry engulfed the Pantglas Junior School with sludgy waste too quickly for anyone to stop what happened next.

The disaster killed 116 children and 28 adults.

"I knew as soon as I came out of the class that my sister was gone," Brian Williams, who was 7 years old at the time, told Wales Online. "You only had to look up the top end of the school and it was just...well, it wasn’t there." Jeff Edwards, who was the last child to be lifted from the school's rubble alive after 90 minutes, told the BBC that he "could hear crying and screaming. As time went on they got quieter and quieter as children died, they were buried and running out of air.”

Aftermath of the Disaster

The rescue effort included first responders, and village residents including the coal miners who ran down to help. Welsh journalist John Humphrys told The Telegraphwhat he saw reporting on the scene: "And there they were when I arrived, their faces still black—save for the streaks of white from the sweat and the tears as they dug and prayed and wept. Most of them were digging for their own children.” Though they continued to dig for a week, no survivors were found after the first day.

The accident was preventable.

Prior to the disaster, Aberfan residents had already voiced concern about the fact that there was essentially an 100-foot tall pile of waste hovering above a school full of young children—even in letters to the National Coal Board (NCB). England's House of Lords launched an inquiry that found the NCB largely responsible for the disaster in a reportpublished the following year. As politician Emlyn Hooson said in 1967, "It was the unanimous view of the Tribunal that this great tragedy could and should have been prevented, and the responsibility fell fairly and squarely on the great public body, the National Coal Board."

However, the NCB refused to acknowledge their role in the tragedy and pay for the remaining colliery tips above the town to be removed; that money had to be taken out of the Aberfan Disaster Fund. According to the BBC, the NCB also first offered only £50 to each parent of a child lost in the landslide, "before raising it to the 'generous offer' of £500."

Queen Elizabeth II allegedly considers her delayed visit her greatest regret.

Prince Philip visited Aberfan on the day after the tragedy. Her brother-in-law Lord Snowdon, who was of Welsh heritage, headed there early that next morning as well. But the queen decided to delay her own appearance there, despite advice to the contrary. In Elizabeth the Queen, royal biographer Sally Bechdel Smith claims this was because she feared her presence would be a distraction to the rescue efforts. "Perhaps they'll miss some poor child that might have been found under the wreckage," she allegedly said.

As depicted on The Crown, Queen Elizabeth II arrived at Aberfan on October 29, 1966 to tour the site and speak with victim's families. Though The Crown paints Elizabeth's reaction as somewhat callous, with Prime Minister Harold Wilson chastising her for the choice to wait, the queen does look duly rattled in photos of her visit with the grieving villagers (on the show, Olivia Colman's queen claims to have faked it).

Members of her inner circle at the time have said the queen does regret not visiting sooner. "I think she felt in hindsight that she might have gone there a little earlier," Sir William Heseltine, who worked in the royal press office at the time, said in the documentary Elizabeth: Our Queen, according to Town & Country. "It was a sort of lesson for us that you need to show sympathy and to be there on the spot, which I think people craved from her."

Per an account published by the South Wales Echo in 2002, Lord Charteris, the Queen's former private secretary, allegedly confided to British author and broadcaster Gyles Brandreth on the matter: "In a diary Brandreth has compiled to mark the Queen's Golden Jubilee year, he recalls a conversation he had with Lord Charteris 10 years ago, asking him if the Queen felt she had ever put a foot wrong - he immediately replied: 'Aberfan.'"

Marjorie Collins, whose 9-year-old son Wayne died in his classroom, told ITV that "people were very pleased that she came here." Queen Elizabeth II has gone back to Aberfan four times since.

Many fans of The Crown say they'd never heard of the Aberfan disaster before.

Despite the horrific scope of the tragedy—and the NCB's despicable lack of response in its wake—the Aberfan disaster is a lesser-known story outside the U.K. Yet those who did know what happened are glad it was shared on The Crown. According to The Guardian, the production team used people who lived in Aberfan at the time, as well as relatives of the deceased, as extras in certain scenes. In an effort to respect their trauma, they were offered counseling by the makers of the show.

Aberfan Today

"We had a therapist to help all the people who were recreating such a horrific scene," producer Oona O' Beirn told The Guardian.“People who live there are still traumatized, of course, and we found they’d never been offered help before. Now we are trying to arrange more.”

The Aberfan disaster was the catastrophic collapse of a colliery spoil tip in Wales on 21 October 1966. The tip had been created on a mountain slope above the village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil, and overlaid a natural spring. A period of heavy rain led to a build-up of water within the tip which caused it to suddenly slide downhill as a slurry, killing 116 children and 28 adults as it engulfed Pantglas Junior School and other buildings. The tip was the responsibility of the National Coal Board (NCB), and the subsequent inquiry placed the blame for the disaster on the organisation and nine named employees.

It was one of the worst industrial disasters Britain has ever seen.

It was the last day of term. 240 children and nine teachers were waiting for their first lesson to begin when a landslide of mud and debris flooded into the classroom.

Phillip Thomas was a ten-year-old pupil at the school and one of the only few to survive the tragedy.

We didn’t know what hit us that day. It’s still hard to believe what did come down. Aberfan should never be forgot.

Although Thomas survived, he was left needing hospital treatment for years to treat a variety of serious injuries.

Another survivor was eight year old Jeff Edwards.

He said that the events of this tragic day had affected him all his life.

What we've all experienced are classic symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. There's no doubt it has affected me on a daily basis. I still have nightmares and sometimes suffer from deep bouts of depression.

Bodies were recovered from the rubble in the days after the disaster by emergency services, rescue teams, tip workers and local residents.

Makeshift mortuaries were opened in local chapels where fathers came to identify their children.

The villagers of Aberfan held a mass funeral six days after the disaster.

A tribunal into the Aberfan disaster found that The National Coal Board ignored repeated warnings that the coal slurry would not be able to withstand a period of heavy rain during the winter, and was very likely to be a danger to the school.

They found that the National Coal Board were to blame for the disaster and the counsel admitted, “It need not have happened and should not have happened if proper site investigations had been carried out beforehand.”

Pantglas School has now been turned into a memorial garden to honour those who lost their lives in the Aberfan disaster.

No comments:

Post a Comment