In 1964, Paul Stephenson walked into the Bay Horse pub in Bristol and ordered half a pint. A bartender served him, but when the pub’s manager noticed, he told Stephenson to get out, saying: “We don’t want you black people in here – you are a nuisance.” Stephenson refused, and the police were called. Eight officers arrived to arrest him for refusing to quit a licensed premises and held him in the police cells until midnight.

The Bay Horse pub may have been notorious for banning black people, but it was not alone. In 1964 it was legal in the UK to refuse service on the basis of someone’s skin colour – and black and Asian people found themselves turned away not just from pubs but from working men’s clubs – and even from housing and jobs.

Stephenson’s one-man sit-in was a way of protesting about this. Stephenson was the first black youth worker in Bristol and fresh from leading a successful boycott of the city’s bus company. For years, the Bristol Omnibus Company had been happy to take money from black and Asian passengers but, backed by its trade union, would not employ black or Asian workers on its buses. The fight to overturn this policy took months and had turned the attention of the whole country to this informal segregation. While the activists had been triumphant, it was not without personal cost: Stephenson had lost his job as a supply teacher for being too “controversial”.

Looking back, the 83-year-old says that the arrival of so many officers in a show of force was the police sending a message about upholding the colour bar – because “they knew I was a civil rights activist”. His subsequent trial became national news. It lasted five days in the magistrates court, with each of the eight officers giving different accounts of the event. What they all agreed on, however, were claims that Stephenson was “aggressive” and had tried to “force his way back into the pub”.

The Bristol Evening Post reported this police line, under the headline: “West Indian leader made a fool of himself.” Thankfully for Stephenson, not everyone was so easily fooled. An Irishman who had been in the pub had witnessed Stephenson’s behaviour and confirmed his account. The charges against him were dismissed and he was awarded £25 in costs.“I was vindicated,” he says, more than 50 years later – and it is clear the decades have not dimmed his satisfaction. After all, this was not just a victory against one pub – following his win, the new prime minister, Harold Wilson, sent Stephenson a personal telegram to say he would change the law. And in 1965, the first Race Relations Act was brought in, outlawing discrimination in public places.

Paul Stephenson was born in Rochford, Essex, in 1937, to a west African father (from whom he was estranged) and mixed-heritage mother, Olive Stephenson (who was herself estranged from her African father). At three years old, he was evacuated to a care home in Great Dunmow in the Essex countryside, with seven white children. He stayed there for seven years, and loved the village so much he “secretly used to weep” at the idea of leaving. He made lifelong friends and spent his time playing in the fields, rabbiting and paddling in streams.

If it sounds like an Enid Blyton novel, it was also complete with the kind of casual racism of those books. He was treated as a curiosity; one of his primary school teachers even cut locks out of his hair to keep as a good-luck charm. When his mother visited the village, people assumed she was a man because she was wearing her Women’s Reserve Army Corps clothes and “they had never seen a black woman in an army uniform”. And when a white woman stared at him in the butchers, exclaiming she “could eat him up”, his terrified five-year-old mind decided this was why there were no other black children in the village.

When he returned to London in 1947, the diversity of the city did not mean he was made to feel less of an outsider. His mother was having difficulty readjusting to civilian life and he remained in care. On his way to school he was confronted with open hostility and shouts of “blackie”, “monkey” and the N-word. After 1948 – when immigration from the colonies began in earnest – the racism only increased. At secondary school he was once more the only black child in his class, but had been somehow transformed from “a cuddly curiosity to a racial threat”. While caning him for a misdemeanour, Stephenson’s teacher asked him: “Why are you looking so black?”

In 1953, he joined the RAF, as a cadet, and served until 1960. It was an important time for his development, he says, and it was here, particularly while posted in Germany, that he started working with young people – children of service people and with the Scouts – which became his life’s work. Later in life, he wanted to give back to the system that had brought him up, and he and his wife fostered eight children.

After the RAF, he went to college to study youth work before moving in 1962 to Bristol to be a youth and community development worker and a supply teacher. Then came the bus boycott. Stephenson, unlike the boycott’s other leaders – Roy Hackett, Guy Bailey, Owen Henry, Audley Evans, Prince Brown – was not from the Caribbean, and he never considered his time in Britain as provisional. This perhaps added extra urgency to his desire to see a more equal British society. He called his autobiography Memoirs of a Black Englishman, because “this has always been my country”, he says now.

That his countrymen did not always recognise this was difficult. Even the Queen Mother, when he met her while serving in the RAF, asked as a first question: “Which part of America are you from?” But he used this prejudice to his advantage when he organised the bus boycott. To confirm the company was refusing to allow black or brown drivers and conductors, the boycotters wanted a test case. So Stephenson phoned the company to secure an interview as a driver, in Bailey’s name. The company assumed his faultless English accent meant he was white, and agreed. But when Bailey arrived, and they saw he was black, he was immediately sent away.

Stephenson was the protesters’ spokesman and won an important legal battle, suing Ron Nethercott, the regional secretary of the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) – which strongly supported the colour bar – after Nethercott had called him “irresponsible and dishonest” in the Daily Herald. Stephenson was awarded £500 in damages, and the case was a declaration that the activists would not tolerate being smeared.

Yet not everyone admired his stance, or his tactics. Bill Smith, of the city’s West Indian Association, insisted the protest “undermined racial harmony in the city”. The Bishop of Bristol agreed, despite Stephenson considering him a friend. Those who did stand on the side of equality paid a high price. Learie Constantinewas a cricketing star turned Trinidad’s high commissioner, and one of the protesters’ most vocal cheerleaders. As a result he was removed from his post by the Trinidadian prime minister, Eric Williams, for getting involved in a “local dispute”.

Accusations of being too radical followed Stephenson for years, but he has no regrets. “You can’t have true racial harmony without racial justice. So, you need to be disruptive.” His activism garnered international attention, and in 1964 he was invited to the US by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

His first stop was New York City, where he met Louis Farrakhan, then Louis X. Stephenson was impressed by his oratory – if not his vicious attacks on Malcolm X, who had left the Nation of Islam a year earlier and would be assassinated in 1965. Stephenson went on to Richmond, Virginia, where he met a surprisingly hostile response at his hotel. The staff and an entirely white lobby of guests turned to stare at him, he says, as if he were a stranger walking into a wild-west saloon. The next day his hosts admitted the reason: the NAACP had secured an agreement to desegregate the hotel and Stephenson was their unknowing test case – the first black man to stay at the John Marshall hotel. He joked: “I thought I’d come to give talks about racism in Britain, not to desegregate the south.”

When the 1965 Race Relations Act came in, the UK government created committees to investigate complaints about breaches of the act. Stephenson worked in this field until 1992. Looking back, he is scathing about their impact. He believes the movement for racial justice was split between those who were co-opted into the government and those who rejected the state and kept pushing for meaningful change through the black power movement. He goes as far as to say it “could have derailed an emerging civil rights movement in Britain”. It took until 1976 to have legislation that criminalised racist actions in employment and housing, and established the Commission for Racial Equality, which could support people in industrial tribunals.

His criticism hits a personal note for me because my mum worked for the Race Relations Board, when she met my dad, who was central in the black power movement in Birmingham. Stephenson also met his wife, Joyce, in movement work, when in 1965 he knocked on her door to ask her to sign a petition on housing in Bristol that he was sending to the House of Commons. They met in May, were married in October and went on to have two children, Paul and Funmilayo.

Stephenson moved to Coventry with the Community Relations Council, but his high-profile role protecting black and Asian communities incurred the wrath of the National Front, members of which threw bricks through his window. The police – angered by his support of the black community’s complaints against them for over-policing, harassment and lack of protection from racist attacks – agreed to send a police car to his home for protection. But they made sure they parked it so that it blocked his drive “just to inconvenience him”. Officers would “stick their fingers up” as they walked by him and the Police Federation even passed a vote of no confidence about his role as a community relations officer. When he left for London in 1972, he was told by several policemen that “a big roar of cheers went up around police stations in the city”.

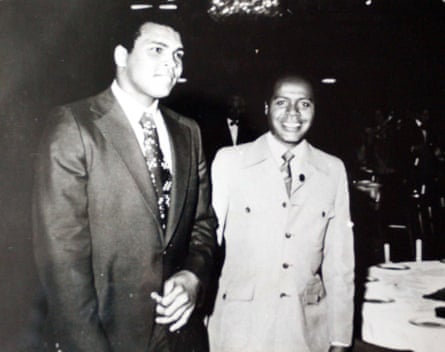

His next move was to sweet talk a superstar. In 1974, Muhammad Ali was staying at the Hilton en route to Chicago after the Rumble in the Jungle – his title fight against George Foreman in Zaire. Stephenson was a governor at Tulse Hill school in Brixton, south London, and decided to take a chance. Walking up to Ali in the lobby – addressing him as Ali when many people still called him Cassius Clay, the name he had dropped years before – he asked him to pay the school a visit. The boxer was pleased he had used his correct name, but when Stephenson said that the school couldn’t pay him, Ali told him he had more nerve than Foreman. Unsurprisingly, all 1,300 students arrived for the assembly and left so enchanted that Stephenson says he still gets stopped in the street by those who remember it.

Ali, he says, was “as you would expect: loud and funny”. To the glee of the watching children, he recited a poem: “I admire your school Mr Stephenson / I admire your style / But your pay is so cheap, I won’t be back for a while.” The two became friends and together set up the Muhammad Ali Sports Development Association (Masda), to give inner-city youth access to sports such as angling and pony trekking. The association attracted the support of black stars including Daley Thompson, Garth Crooks, Arthur Ashe and John Fashanu, but also took a political stance. In 1982, Masda launched the British Standing Conference Against Apartheid Sports, with the support of the World Boxing Association (WBA) champion Lloyd Honeyghan. Honeyghan threw his belt in the bin when the WBA sanctioned fights in apartheid South Africa while, according to legend, Stephenson’s staunch anti-apartheid stance led Margaret Thatcher to view him as a “terrorist sympathiser”.

In 1992, Stephenson returned to Bristol with his wife, fostering children and campaigning for the city to face up to its links with slavery. He says the continued plastering over the city of the name and image of the slave owner Edward Colston is a “reminder that racism is alive and kicking”. As for the toppling of the slave owner’s statue this year, that should be a wake-up call to the establishment that “change will come one way or another”. For all that has been achieved in his lifetime, Stephenson is worried that the “law has changed and little else”. We are at a crossroads, he says, and he can only hope that the government and British society will finally listen to “cries for justice”.

In 2008, the man who spent hours in a Bristol jail cell for buying a drink in a pub became the first black man to be made Freeman of the city – a testament to the struggles that have gone before and the work left to be done.

Source :The Guardian UK

No comments:

Post a Comment